The ARD Meeting That Broke the Silence—and the Trust

ARD meetings can be intimidating for parents, and this can be even more true when the parent does not speak English. To support these families, the ARD committee includes an interpreter to ensure parents can make informed decisions about their child's placement, progress on goals, and preparation for the future. In these meetings, every member of the team has a voice, and no voice is more important than another.

This meeting began like so many others. Everyone was present. We opened with introductions, reviewed the confidentiality statement, and I gave my usual explanation—adapted for each student—about the eligibility categories that qualify the student for special education. I shared: “Your student qualifies for special education due to meeting criteria as a student with autism and a speech impairment.” I continued, describing how these needs impact the student’s education.

Mic drop.

The parent turned to the interpreter and began speaking rapidly in Spanish.

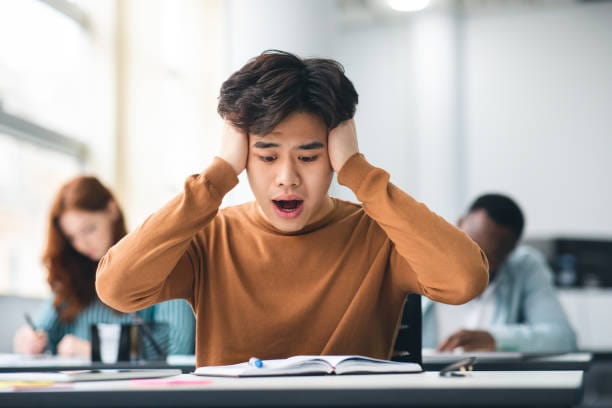

The student—sixteen years old—looked at me and asked, “I have autism?”

His older sibling quickly interjected, saying I must have made a mistake.

I was stunned. This wasn’t an elementary student or even a middle schooler. This was a young man just two years away from adulthood learning—for the first time—that he has autism.

The interpreter explained that the parent had intentionally chosen not to tell him. She feared it would upset him. She didn’t want him to feel “labeled” or limited.

Let’s set aside the fact that this is something that would have been important to communicate before the meeting.

Let’s set aside that this young man is two years from adulthood and should already be contributing to his educational planning.

Let’s set aside that the parent was trying to protect her child.

The student was devastated. He asked why everyone had been lying to him for years. The look he gave his family was heartbreaking—full of betrayal and broken trust.

We finished the meeting, and the family left. I can only imagine how tense that evening must have been.

What we learned:

Families have a legal right to information about their child’s disability—but students do not gain full legal access to their own educational records and evaluations until they turn 18. This gap can create situations where well-intentioned parents withhold information, believing they are protecting their child, while unknowingly limiting their self-understanding, autonomy, and readiness for adulthood.