Safe Enough to Sleep

I was a special education teacher in a juvenile detention facility for two years at a maximum-security correctional center in Golden, Colorado. My task was to start a self-contained program for the most severe, disruptive, and violent students who qualified for special education services.

Emanuel was one of those students—a super senior who still needed many credits to graduate. He could be cheerful and helpful one minute, then explosive the next. He was considered one of the most violent youth in the facility and had a long history of aggression toward staff. Relationships, whether with peers or adults, were difficult for him, and authority figures often triggered defiance or rage.

When Emanuel first entered my classroom, he developed a routine that was anything but typical. Every morning, he would come in, stretch out on a hard, uncomfortable wooden bench, and fall asleep—sometimes for two or three hours. Then, as if nothing were unusual, he would wake up and complete all the assignments he’d missed while asleep.

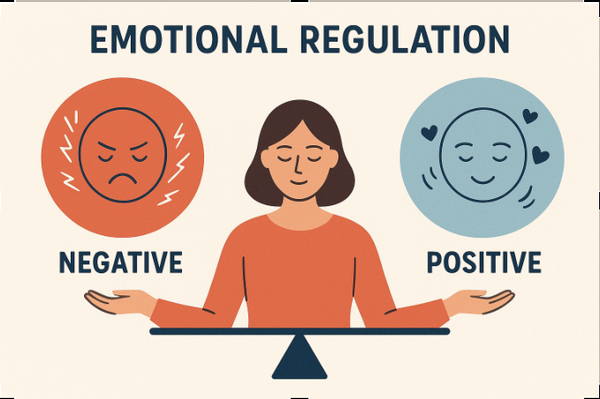

Over time, I began to see something shift. Emanuel started asking for help with his work. He helped other students who were struggling academically or behaviorally. Within a few months, he became the star student of the program—motivated, respectful, and focused on credit recovery so he could graduate. The paraprofessional and I often marveled at the transformation. Emanuel volunteered for every extra assignment and took great pride in working with the grounds crew to keep the facility clean and beautiful.

One day, Emanuel explained his strange morning routine. He told us that he was too scared to sleep at night on the pod because he never knew what might happen. Hypervigilance had become his survival strategy. The classroom was the only place where he felt safe enough to rest.

Despite the progress we saw, not everyone believed it. One day, a security officer approached me and said that Emanuel was “faking his compliance” and “just trying to get one over on us.” It was clear that some staff struggled to accept that genuine change was possible in these students.

But Emanuel proved them wrong. He graduated high school and transitioned into a continuing education program focused on lawn care. I can still picture him mowing the grass, planting flowers, and taking pride in making the facility beautiful.

What we learned is that every student has the potential to internalize positive experiences and begin to see themselves differently than others see them. When given safety, trust, and opportunity, those changes can be life-changing—even when the world refuses to believe they’re real.